This situation is unavoidable as my place, Negros Oriental, is in a tropical climactic zone - sunny, humid, and plenty when it comes to rainfall - which promotes intense chemical and biogenic weathering. This in turn accelerates the processes of soil formation.

But actually (as I have realized from one of my great epiphany moments), you could use soil maps, and a little knowledge of pedology (the study of soils), to aid you in uncovering the lithology of an area!

Here is how I intend to use this new-found knowledge in one of my assigned work in our Principles of Stratigraphy class.

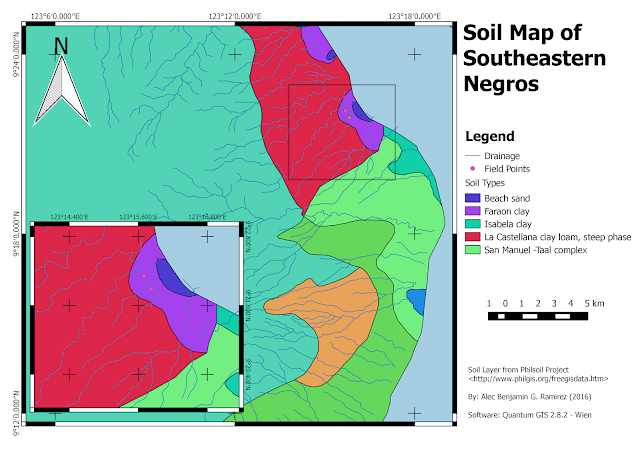

As you could see below, the area I am concerned about (labelled Field Points) has a soil cover made up of the Faraon clay variety.

Consulting an authorized literature, such as the Simplified Keys to Soil Series - Negros Oriental (Philippine Rice research Institute, 2014), the Faraon clay series is "a calcareous, fine-textured soil with less than 65% clay, developed from the weathering of the soft and porous coralline limestones..."

Because of this verification, we can now infer from the soil map that those areas covered by the Faraon clay is underlain by either a limestone cap, or a calcareous conglomerate bed.

Of course, this method of inference can only be used for residual (or authigenic) soils, which are formed from the weathering of the rock at source itself. In contrast with the allogenic soils, which are transported from another place, the soil type would tell the lithology of the source of the soil itself.

There are many other ways to incorporate soil maps in geologic analysis. Arguably, they are important tools that student geologists should be familiar about them.

As you could see below, the area I am concerned about (labelled Field Points) has a soil cover made up of the Faraon clay variety.

|

| Picture 1. The Soil Map of South-eastern Negros |

Thus, without going to the field, I now have an idea about the lithology of the area I am studying, that is, it is composed of coralline limestones. This means that this area has been underwater, as coralline limestone are only deposited in shallow marine environment.

But of course, verification must be achieved if possible. Below, you could see a picture of a building stone and sand quarry in the area, which shows the subsurface strata.

But of course, verification must be achieved if possible. Below, you could see a picture of a building stone and sand quarry in the area, which shows the subsurface strata.

Of course, this method of inference can only be used for residual (or authigenic) soils, which are formed from the weathering of the rock at source itself. In contrast with the allogenic soils, which are transported from another place, the soil type would tell the lithology of the source of the soil itself.

There are many other ways to incorporate soil maps in geologic analysis. Arguably, they are important tools that student geologists should be familiar about them.